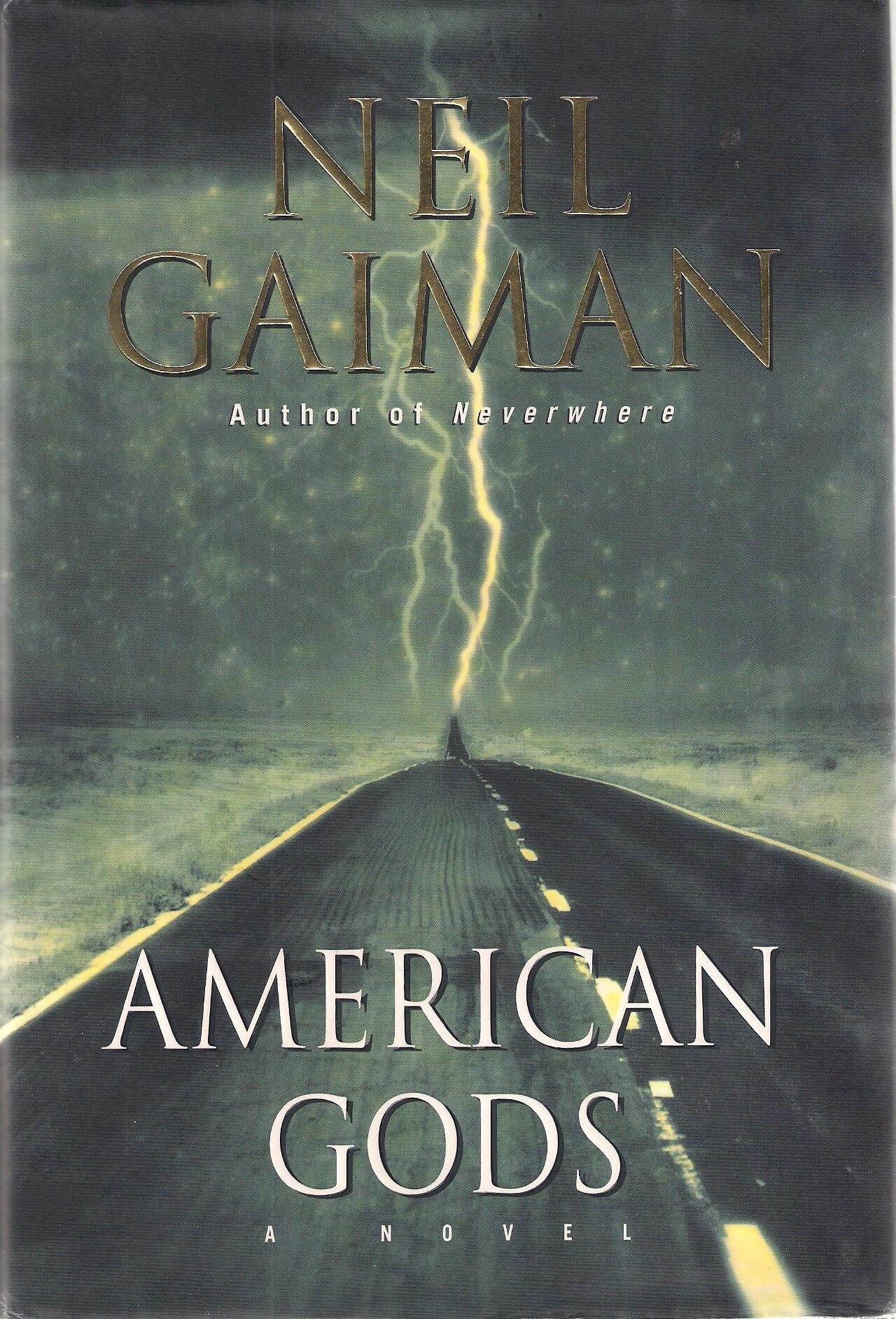

Just finished reading Neil Gaiman’s American Gods, the premise of which I found interesting although the book suffers from several problems. One is the rampant passivity that plagues most modern fiction—i.e., the main character has lots of things happen to him without proactively affecting the plot, and hence spends most of the book in utter confusion somewhat akin to that of a lab rat, a problem Robert E. Howard, despite his many artistic faults, seldom manifests. Also, much of American Gods, clever and well-written as it often is, is penned in a spare and hyper-visual style just like comic scripts or movie screenplays I’ve read, which serves certain scenes well but ultimately detracts from the epic Lord of the Rings/The Stand quality of the journey. And the plot is somewhat reduced in thematic terms by the gaping hole where Jesus should be, something that I think needs to be addressed in any book that lays claim to discussing Americans and their gods, both historical and modern. Still, the sheer phantasmagoric imagination at work here and the courageous “swinging for the fences” mentality that seems to drive the ideas lends gravitas to the book and validates the many awards it won upon its release in 2001. In a genre as stagnant and repetitive and filled with terrible writers as fantasy, Gaiman stands out as a talent worth reading and analyzing.

Just finished reading Neil Gaiman’s American Gods, the premise of which I found interesting although the book suffers from several problems. One is the rampant passivity that plagues most modern fiction—i.e., the main character has lots of things happen to him without proactively affecting the plot, and hence spends most of the book in utter confusion somewhat akin to that of a lab rat, a problem Robert E. Howard, despite his many artistic faults, seldom manifests. Also, much of American Gods, clever and well-written as it often is, is penned in a spare and hyper-visual style just like comic scripts or movie screenplays I’ve read, which serves certain scenes well but ultimately detracts from the epic Lord of the Rings/The Stand quality of the journey. And the plot is somewhat reduced in thematic terms by the gaping hole where Jesus should be, something that I think needs to be addressed in any book that lays claim to discussing Americans and their gods, both historical and modern. Still, the sheer phantasmagoric imagination at work here and the courageous “swinging for the fences” mentality that seems to drive the ideas lends gravitas to the book and validates the many awards it won upon its release in 2001. In a genre as stagnant and repetitive and filled with terrible writers as fantasy, Gaiman stands out as a talent worth reading and analyzing.

It occurred to me that the book’s main fantasy—that all the Gods of history were brought to America in the minds of its immigrants and were then forgotten, leaving them to get by in America as near-mortal, on-the-skids versions of their previous godlike selves, albeit ever on the lookout for a comeback—can be applied to authors as well. Gaiman himself seems to have unwittingly made this connection, as the following excerpt from one of his press tour interviews shows:

1930. Probably the most prominent English essayist was A. A. Milne. The editor of Punch, famed for his comedic essays and a man with several plays running in the West End concurrently. A man who had bestselling books with titles like The Daily Round and hilarious collections of essays and sketches. One of the funniest writers of his generation and an accomplished playwright. I did an Amazon search several months ago just out of interest to see just what of his was actually in print. And it listed 700 books: all of which, as I went down page after page, were variant editions of the two Winnie the Pooh books and the two books of comic verse for children that he wrote. And that’s all that we have left of A. A. Milne and he’s in better shape than most of his contemporaries whose names we do not remember at all. I can’t point to the other guy who was the biggest playwright in the 1930s because we don’t know who that was and if I said his name, you’d be blank. The fact is, those two books of children’s stories and two volumes of children’s verse are what posterity, rightly or wrongly, has deemed the important thing to remember about what A. A. Milne did.

Like the gods of Gaiman’s imagination, authors go through periods of sometimes incredible power and influence, which can continue for decades or for millennia, depending entirely on the necessity of “worshippers” continuing to praise and honor them. It’s the reason why Charles Willeford, in Don Herron’s biography Willeford, maintains so forcefully that “writers need critics.” It’s why, in both Gaiman’s novel and in his example above, even the Great hold power only at the pleasure of the masses. Once the people stop worshipping, the power of the god, and indeed the god itself fades. It’s still there, buried in the psyche of a few, popping up now and again in some minor fashion or historical context, but the fame and influence that once was is no more.

Seen in this light, Robert E. Howard’s borderline obscurity takes on a new, more optimistic meaning. Like Milne, he has seen better days, and also like Milne, he is largely now known for a single creation, Conan. But it’s clear that, seventy years after his death, Howard has a much broader range of material in print than “most of his contemporaries whose names we do not remember at all,” as Gaiman puts it. Even Howard’s minor characters have fan followings and reprintings via books like Paul Herman’s Wildside volumes. Howard is, most definitely, not forgotten, or in mortal danger of being lost to the ages like his contemporaries, many of whom inspired and influenced him. Given the extremely low percentage of authors that make the jump to posthumous relevance and success, I like Howard’s chances to remain a viable force in fantasy, and a growing one in classic American literature.

Later in his interview Gaiman notes that it’s far too early to tell if he himself is going to be remembered for anything, despite his classic Sandman series of comics selling upwards of 80,000 copies in hardcover collections each year, almost twenty years after they debuted. Or perhaps—like Milne—one of Gaiman’s minor works will be the one thing everyone remembers his name for long after he’s gone. That’s exactly right, and exactly what many people do not understand about the long-term prospects of writers. When the current crop of popular authors have been dead for seventy years like Howard, then you can talk about who’s selling what and who is more famous than who. With living authors sales count precious little towards their long-term critical or artistic viability. But with dead authors, continued sales become much more important. Howard’s work has outlived the hugely popular works of far more successful authors, for far longer than such authors have been on the cultural map. Selling millions of copies and being highly collectible seventy years after your death is a high achievement. It’s rare. It means something.

As American Gods go, Robert E. Howard is not too shabby.