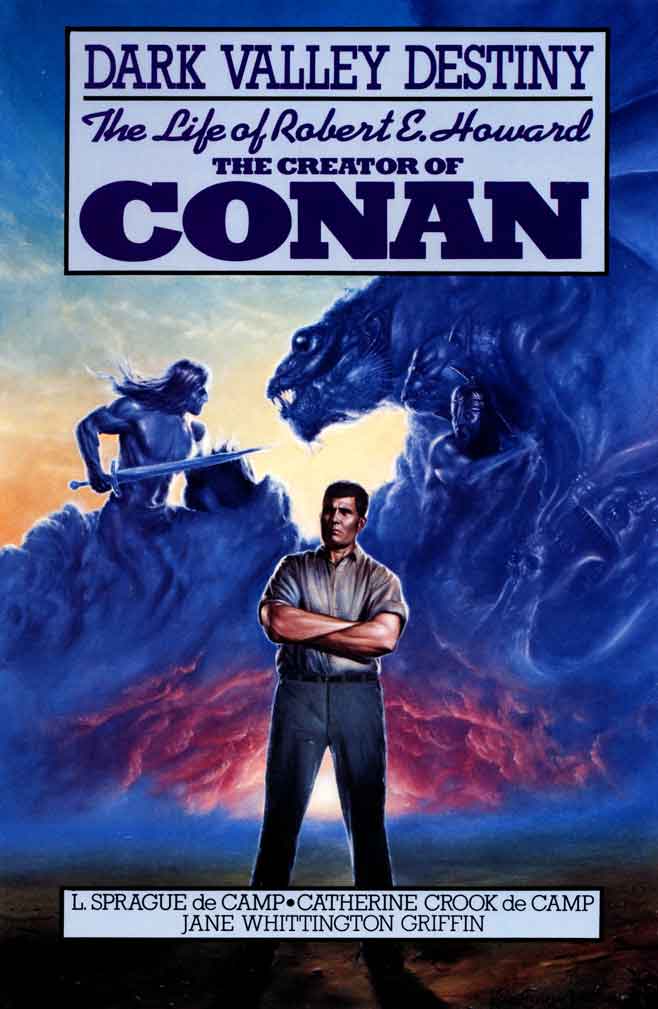

When I recently picked up the hardcover edition of Dark Valley Destiny by L. Sprague de Camp, Catherine Crook de Camp, and Jane Griffin (Bluejay Books, 1983) for the hundredth time, a quick perusal of the dust jacket copy suggested a number of thoughts.

When I recently picked up the hardcover edition of Dark Valley Destiny by L. Sprague de Camp, Catherine Crook de Camp, and Jane Griffin (Bluejay Books, 1983) for the hundredth time, a quick perusal of the dust jacket copy suggested a number of thoughts.

The first was one I never heard anyone else mention before, namely that it’s risible that two thirds of the triad that penned the only biography to date on Robert E. Howard were women, and antipathetic women at that. While I of course have known this factually for many years, this observation had never struck me with such force before. Try as I might, I find it impossible to escape the conclusion that dissecting the life of Howard, one of the all-time classic men’s writers, requires a sympathetic and understanding male outlook and empathy far beyond what a pair of old ladies like Mrs. de Camp and Mrs. Griffin could ever hope to either possess or compensate for.

The dust jacket copy of Dark Valley Destiny is also a microcosm of both the pleasures and the problems inherent in the book. It begins, as de Camp’s ruminations on Howard almost always did, with noting the suicide, stating:

On the morning of June 11, 1936, thirty-year old Robert E. Howard ascertained from his mother’s nurse that Mrs. Howard would not regain consciousness. He had spent the night before sorting through his papers; he had made funeral arrangements earlier in the week. Then he calmly walked out the door, got into his car, carefully rolled up the window, and shot himself in the head. Thus ended the life of one of America’s most significant writers.

Such a preternatural focus on the suicide to the exclusion of all else is a large part of what infuriates so many fans about de Camp’s book. But tellingly, the dust jacket then goes on to heap ample praise on Howard in unabashedly admiring terms. “The definitive biography of Robert E. Howard, who created the archetypical fantasy hero … the heroic sweep of his narratives, the vividness of his imagery, and his ability to convey mood, magic and mystery mark his writing as exceptional. Had he lived, he might have become one of the most celebrated of all American fantasy writers.” That he actually has become one of the most celebrated of fantasy writers shouldn’t cause us to judge this last statement too harshly; Howard fans have well-documented the penchant of critics to leave Howard out of books on the fantasy genre, despite his preeminent status. On those grounds, the statement that Howard “might have” become celebrated is valid.

The various analytical statements that follow the above praise, describing how the de Camps and Griffin have masterfully delineated “Howard’s problems,” should be weighed against the remark that “Dark Valley Destiny is a fascinating work of research, interpretation and writing that illuminates the personality of the man who, almost singlehandedly, created the subgenre of American fiction now called `heroic fantasy.”‘ The italics in “interpretation” are mine, intended to highlight one of the stated techniques de Camp used to flesh out the shadowy areas in Howard’s life, one of the techniques that any biographer has to use when a vast swath of the subject’s life is mist. De Camp can surely be criticized for the logic and strength, or lack thereof, of these interpretations, but let us not damn him for the necessity of interpreting in and of itself.